Visit the WoH Archives!

History of Hope

In order to understand where an organization is going, it’s important to understand where the organization has been. The foundation of the humanitarian organization, Wings of Hope, rests on the shoulders of many individuals aiming to make the world a better place — to shine a ray of light in places that are obscured by shadows and seem to be forgotten by the rest of civilization. Wings of Hope is a concept born in the hearts and minds of those who strived to extend a nurturing hand to those in need. It’s a sense of patriotism magnified to a grand global scale, where no religious and political boundaries exist. The only thing that matters, as we march forward in this life, is to make sure that no man, woman, or child is left behind.

Crisis in the Turkana

We can trace the history of Wings of Hope to 1959 in the Turkana, a desert region in northwest Kenya. It was a year of a terrible drought. Four out of every five camels and goats were wiped out. Then came the rains, which caused massive flooding. Even after the flooding stopped, the depletion of animal herds threatened the people’s existence. Government relief camps provided scant support, prompting Nairobi officials to grant missionaries access to the region in 1961.

The Catholic missionaries poured in, and among them was Mike Stimac of the Medical Missionaries of Mary. Stimac quickly realized that transportation was one of the biggest obstacles to getting help to the people. Just traveling between Lodwar and Kitale, 140 miles by plane, was a 15-hour journey by jeep!

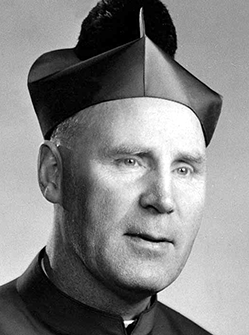

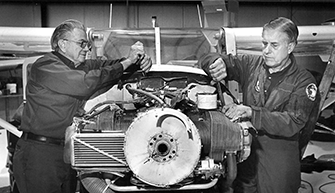

Jerry Fay, a pilot for Pacific Northern Airlines, connected Stimac with Bishop Joseph Houlihan, whose diocese spanned the Turkana. Houlihan talked with Fay about using light aircraft to transport people and supplies across the desert, an expansive area encompassing over 36,000 square miles. After discussing the myriad challenges, including a non-descript desert landscape that makes flying disorienting and dangerous, the two men launched a plan to bring a plane to Kenya. Fay recruited Pacific Northern co-worker and friend Everett (Bud) Donovan to travel with him to Africa to set up the new program. Then, they established the Marian Medical Airplane Fund to raise the $11,000 needed to buy a new Piper Super Cub 18A. Neither anticipated that raising the capital for the plane would be far easier than actually getting it to its destination. In February 1963, they shipped the plane in a crate from Piper Aircraft in Lock Haven, Pa., to Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. The journey was fraught with delays, but after several weeks, the plane finally arrived at Ethiopia ready for assembly.

Donovan made quick work of building the Piper Super Cub. Just four days after it arrived, he was flying it 130 miles south of Addis Ababa to scout for scarce aviation resources.

“After I had made a landing in a deserted area near Lake Awassa, one of the plane’s tires rolled off,” Donovan said. “I walked nine miles before I found a radio station so I could report that I was alright. I then walked back, fixed the tire and flew back to Addis Ababa.”

The next leg of the journey was a 700-mile trip to the Kenyan capital Nairobi, where Wilkins Air Service would provide all the maintenance and parts needed to keep the Piper flying. Over the next three weeks, Donovan would fly over 80 hours – moving supplies to mission stations and educating the missionaries about the aircraft.

During their time in Turkana, Fay and Donovan were pleased with the progress they saw: new buildings being erected for hospitals and schools, and supplies moving efficiently throughout the six mission locations. It would now truly be possible for the missionaries to implement their strategy of first providing food, then medical attention, and then education.

“We were convinced that air transportation is the only answer to the mission-supply problem in Africa,” both pilots said. “We can see where this small effort of ours proved this. And we hope we will be able to get this message across this country to those who have a means to supply the air transportation.”

Flying Nuns

As Stimac was in Kenya training two nuns to fly the plane, Sister Michael Therese Ryan completed her flying course in Boston. She passed her pilot exam on the first try, earning the distinction of becoming the first Catholic nun to do so. Sister Ryan (a.k.a. “The Flying Nun” and “Sister Bird”) would log over 40 solo hours before making her way to Kenya, where she would ferry supplies from the central hospital in Eldoret to three camps, some 800 miles apart. The sisters would fly missionary doctors, nurses, patients, medical supplies, and anything else that was needed. Soon they were dubbed “The Marianist Air Force” – and stories about “the flying nun” appeared in international newspapers.

UMATT

While Sister Ryan’s single-plane operation was improving the lives of the Turkana one flight at a time, Stimac dreamed of a fleet of airplanes linking all of the missions scattered across the famine-stricken desert. During the summer of 1963, Bishop Houlihan came to the United States to raise money for the Turkana famine victims. St. Louis businessman Bill Edwards invited Joe Fabick of Fabick Tractor Company and other guests to his home to listen to the Bishop’s presentation. Houlihan narrated as the amateur 8mm film showed the starved and sick natives in the Turkana and Sister Bird flying the Super Cub. It also showed the Piper’s deteriorating condition caused by harsh desert conditions and hyenas gnawing on the fabric wings. These images had a profound effect on the attendees — none more so than Edwards and Fabick. The two friends quickly made it their mission to get the missionaries a durable, metal airplane equipped for bush flying. To help raise money for the cause, they brought on board Paul Rodgers, V.P. of Ozark Airlines, and publisher George Haddaway, who happily used his Flight Magazine to create awareness and solicit donations.

The fundraising was successful, and on April 25, 1965, Father Houlihan was finally able to get his metal winged aircraft: a Cessna U206. More than half of the $30,000 raised came from non-Catholic sources, a testament to the fact that this effort transcended religion and inspired universal support. On May 25, Catholic, Protestant and Jewish leaders met at the Ozark Airline hangar at Lambert Airport in St. Louis to see off legendary long-distance pilot Max Conrad as he prepared to ferry the 206 to Kenya. The plane would stop for similar sendoffs in Dayton, Ohio; Boston; Shannon, Ireland; and Rome, where it was blessed by Pope Paul VI.

When the plane finally landed in Nairobi on June 10, Edwards and Fabick handed the Cessna’s keys to Stimac and Thomas Dwyer, the co-founders of the newly formed United Missionary Air Training and Transport — or UMATT.

“This double-door work plane with a 285 horsepower Continental motor has been donated by friends of aviation and of missionary endeavor.”

Joe Fabick

In what now seems an obvious foreshadowing, the UMATT logo painted on the Cessna’s tail wing featured a dove: a symbol of peace and hope.

The Birth of Hope

As stories about UMATT garnered widespread international attention, requests for airplanes inundated the St. Louis group. This sparked many discussions between Edwards and Fabick about finding creative ways to use general aviation to support humanitarian efforts. They began by expanding their core St. Louis group to include Rodgers (V.P. of Ozark Airlines) and Haddaway (Flight Magazine publisher) — and Wings of Hope was born. (This core group later grew to include Dr. John C. Versenal, DDS, Oliver Parks, founder of Parks College of Engineering, Aviation and Technology, Tom McCarthy, Jim Holton and Dave Kratz.)

Wings of Hope officially incorporated on July 17, 1967, as a nonprofit organization. The organization would be humanitarian, non-political and non-sectarian. It would serve any qualified group dedicated to helping disaster victims and people in need.

Each founding member of Wings of Hope set out to promote the new entity the best way he could. Joe Fabick pursued donations that would provide tax write-offs for items people no longer wanted. He accepted old road graders, backhoes and bulldozers from customers and other companies in the construction business, giving credit for trade-ins. His Fabick Tractor Company would then refurbish and resell these items and give the money to Wings of Hope. George Haddaway ran publicity articles about Wings of Hope and contributed advertising space in his magazine. This spurred an influx of membership donations from pilots and offers to help from a growing pool of invaluable volunteers. Bill Edwards pursued businessmen as donor-members, taking advantage of his contacts as a manufacturing agent and his membership in the St. Louis Missouri Athletic Club.

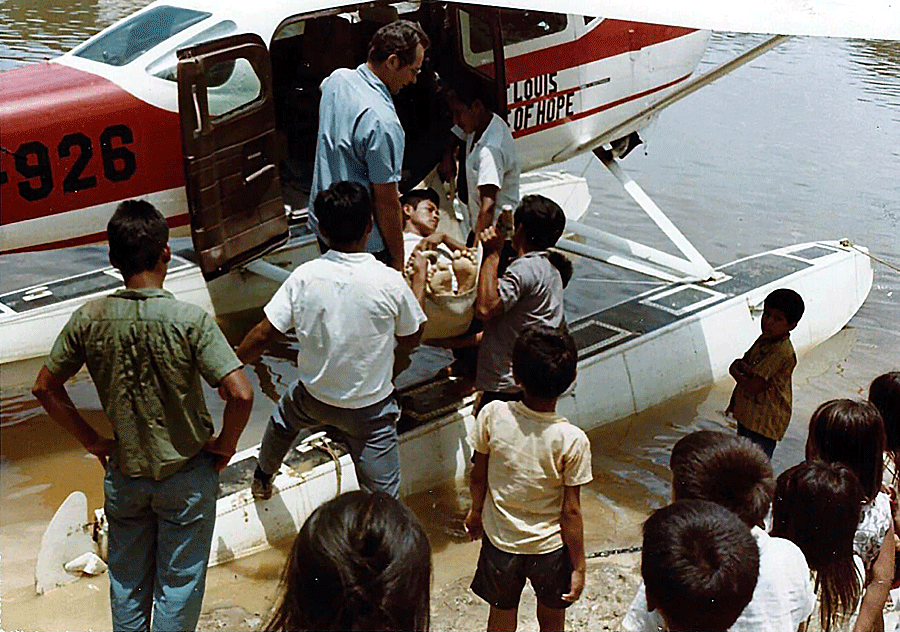

On January 17, 1969, Wings of Hope was declared tax-exempt under section 501(c) (3) of the Internal Revenue Code. In May of that year, the charity purchased two more aircraft and put them into service in Peru and New Guinea. As Wings of Hope extended its geographical reach, its reputation began to attract the notice of highly influential people. Of note was Neil Armstrong, who sent a letter to Bill Edwards on September 19, 1969, that said, in part:

“I certainly want to send my congratulations on your efforts on behalf of Wings of Hope. I am certain that this valuable project is achieving brotherhood between nations in a way that cannot be accomplished by diplomacy or government aid programs. As an aviator, I sincerely salute this fine service as being one of the best achievements of the combination of general aircraft and dedicated individuals of good will.”

Neil Armstrong

In the 1970s, Wings of Hope continued to expand into more areas in Africa, South America, Alaska, New Guinea and Central America. But the mission remained constant. As Joe Fabick wrote in a Wings of Hope newsletter in the spring of 1974:

“In the years ahead, Wings of Hope will continue to provide services exactly as they always have: free of charge as an inter-faith organization serving the cause of international brotherhood.”

Joe Fabick

A Timeless Mission

More than 40 years after he wrote them — and 50 since Wings of Hope was founded — Joe Fabick’s words still ring true. Wings of Hope started as one man’s dream to use aviation to help the world’s most neglected people. While the scope and scale of the organization has expanded and evolved since those early days, the mission has remained as pure as when it was first conceived.

The mission hasn’t changed, because the need hasn’t changed.

“There is always somebody isolated and forgotten who needs help gratis … who needs hope, peace and life.”

Wings of Hope volunteer pilot, Guy Gervais (November 11, 1973)

Wings of Hope exists to answer their cry for help.